A warning against romanticism in military planning.

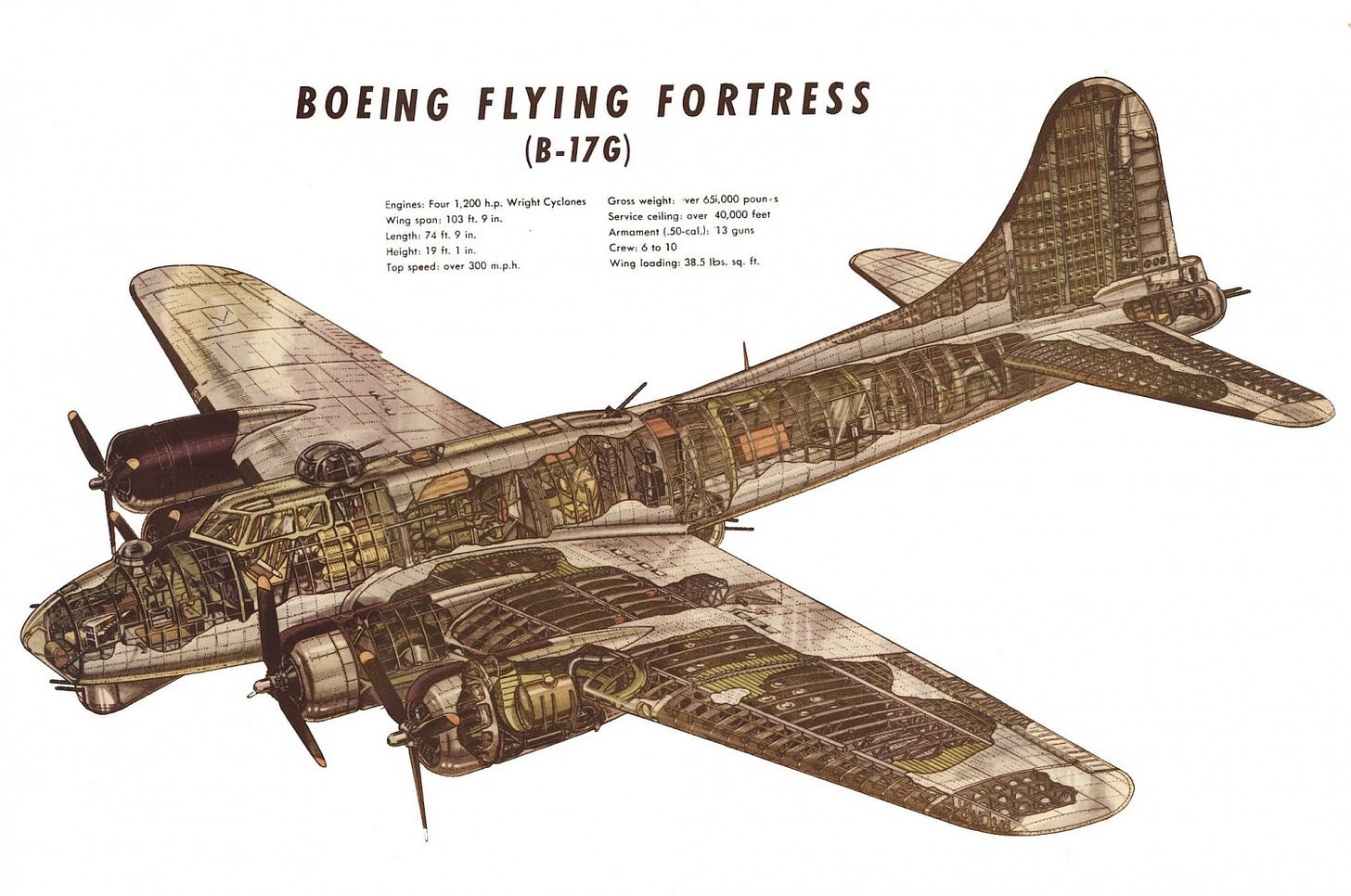

In the early 1940s, the US Army Air Corps (USAAC) made a fateful decision that would cost the lives of tens of thousands of men over the next decade. Two years prior, the Army had just begun testing her newest bomber, the XB-17. This was not yet the slow, gun-festooned B-17 that would go down in legend as the chariot of the 8th Air Force in World War II. Rather, this Boeing marvel was the fastest plane in the world, setting a nonstop speed record from Washington to Ohio of 252 miles per hour in 1938. Where the familiar B-17 lumbered towards its target with a hedgehog assortment of 13 machine guns in 8 manned positions, the early B-17 was optimized for low drag, low unladen weight, and high altitude high speed flight. As it was developed into the Y1B-17, B-17A, B, and C models, the aircraft became faster and able to fly even higher through constant engine upgrades, eventually resulting in a plane that by mid-1940 could fly at over 320 miles per hour, and reach heights of 37,000 feet. The B-17C was powered by four 1,200 horsepower Wright R1820 Cyclone radial engines, each of which could have by itself powered a top of the line fighter aircraft of the period.

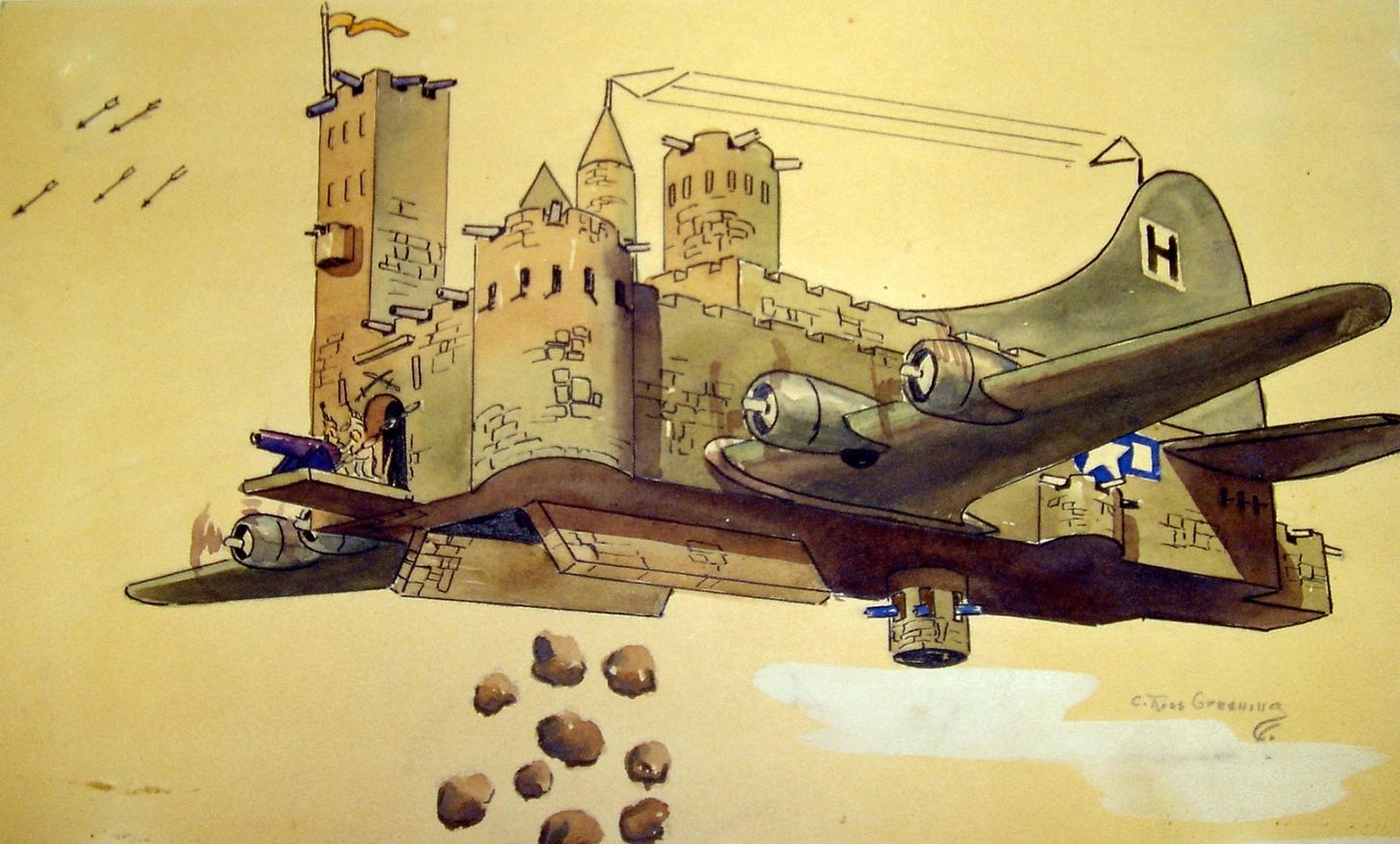

Yet, by 1940 the US Army faced a dilemma: The B-17 provided unequaled long range to attack targets over 2,000 miles away, but no USAAC fighter at the time had the legs to escort the new long range bombers. If the B-17s came under attack from enemy interceptor fighters, there would be no friendly fighters to engage them. At the same time, the pace of development in the late 1930s and early 1940s was such that the formerly record-setting B-17 was now slower than the newest fighters expected to intercept it. The Army brass decided on a solution: The bombers would be modified with integral air defense machine gun emplacements. In doing so, they believed that the bombers could shoot down any intercepting fighters themselves, without the need for fighter escort. By arranging the bombers into protective formations, the fields of fire of their guns would “interlock” like those of Maxim guns over the trenches of World War I. And like poor troops on the advance in that war, any intercepting fighters would be met with a “wall of lead” that made the bombers too prickly to successfully attack. So went the theory.

In practice, the concept backfired badly. Every gun emplacement added to the B-17 increased both its weight and drag, reducing the maximum speed and altitude of the aircraft. The iconic B-17G model was a full sixty miles per hour slower than the already ‘too slow’ C model, which gave enemy fighters that much more time to intercept and attack their formations. Versus German anti-aircraft (FlaK) cannons, the defensive armament was useless, and the lower top speed only made them easier prey. To add to the problem, its defensive armament was not very effective at destroying enemy aircraft, either. The AN/M2 Browning .50 caliber machine guns fired M8 Armor Piercing Incendiary (API) ammunition, which carried just 15 grains (1 gram) of IM-11 incendiary compound – not enough to reliably ignite the self-sealing fuel tanks and other vulnerable structures on most enemy fighters. Further, the additional gun stations required another 4 crew in addition to the 6 mission critical crew. This not only meant that the bomber formations carried 67% more personnel into harm’s way than they otherwise would have, but those crew were spread out into more vulnerable parts of the aircraft. A minor hit to the tail of a B-17C might affect the maneuverability of the plane; a similar hit to the tail of a B-17G could kill any of three tail gunners.

Despite these downsides, the USAAC stuck to their guns through the end of the war. The result was a massive death toll. 26,000 8th Air Force personnel were killed in action, more than 20,000 more were injured. More 8th Air Force crewmen were killed in action than Marines in the entire war, and they made up half the total death toll of the Air Force in World War II. Though the bombing campaigns on Europe were ultimately successful, the high cost of the USAAC’s strategy has led to it being considered, in hindsight, a failure.

The concept of “flying fortress” bombers with large crews is an extremely compelling idea. By its nature, it stimulates the imagination with visions of men fighting together in the bond of war to defend their home against the enemy’s assault – and that home is flying through the sky itself. The alternatives, like building faster bombers, or conducting raids only at night, don’t carry the same romance. The death toll, though, speaks: Such romanticism can be dangerous. Yes, the generals who made that fateful decision had their reasons, and surely thought they were doing the right thing, but such ideas tend to capture the hearts of men – and when they do, they are difficult to shake.

As the challenges the Army faces evolve, the field of small arms will have to change with it. In the near future, the pace of technological development will bring with it forks in the road which must be navigated by steady hands. The idea of long-range “overmatching” infantry is also, like the fortress bombers of the Forties, an inherently romantic concept. When faced with entrenched enemy machine guns at long distances, it is far more gallant-seeming to shoot back than to call for air support. It’s easy to see more honor in using a rifle to zap a foe dead at the better part of a kilometer than in wielding radio first and rifle second. The potential for error here is obvious, however: Anyone so compelled by the concept’s vision will likewise be blind to its pitfalls, and deaf to any warnings against it. And the consequences of error? The 8th Air Force serves as a reminder of what those can be.